According to Standard Life Investments, the US Dollar will be one of the top currencies in 2011. (The other currency they cited was the British Pound). How can we understand this notion in the context of record high gold prices and commentary pieces with titles such as “Timing the Inevitable Decline of the U.S. Dollar?”

The Dollar finished 2010 on a high note, both on a trade-weighted basis and against its arch-nemesis, the Euro. Speculators are now net long the Dollar, and according to one analyst, it is now fully “entrenched in rally mode.” Never mind that its performance against the Yen, Franc, and a handful of emerging market currencies was less than stellar; given all that happened over the last couple years, the fact that the Dollar Index is trading near its recent historical average means that the bears have some explaining to do.

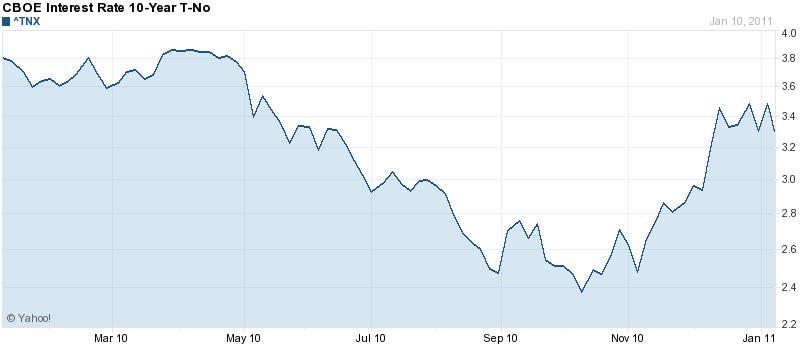

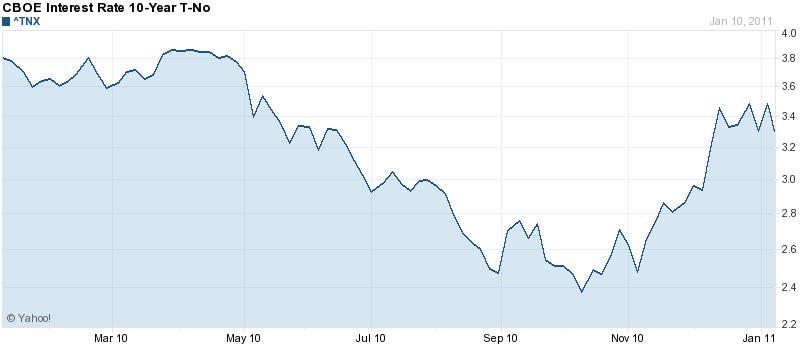

To be sure, none of the long-term risks have been addressed. US public debt continues to surge, and will not likely abate in 2011 due to recent tax cuts. Short-term interest rates remain grounded at zero, and long-term yields have only just begun to inch up, which means that risk-taking investors still have cause to shun the Dollar. Ironically, signs of economic recovery in the US have reinforced this trend: “The [positive economic] data, which one would ultimately assume is positive for the U.S., looks better for risk, which in turn puts downward pressure on the dollar.” Finally, the the Financial Balance of Terror makes the US vulnerable to a sudden decision by Central Banks to dump the Dollar.

So what’s driving the Dollar in the short-term? The main factor is of course continued uncertainty in the Eurozone over still-unfolding fiscal crisis, which is directly driving a shift of capital from the EU to the US. Next, the budget-busting tax cuts that I mentioned above are predicted to both boost economic growth and make it less likely that the Federal Reserve Bank will have to deploy the entire $600 Billion that it initially set aside for QE2. (To date, it has spent “only” $175 Billion in this follow-up campaign, compared to the $1.75 Trillion that it deployed in QE1). According to The Economist, “JPMorgan raised its growth forecast for the fourth quarter of next year to 3.5% from 3% as a result [of the tax cuts]. Macroeconomic Advisers, a consultancy, says the new package could raise growth to 4.3% next year, up from its current forecast of 3.7%.”

In fact, long-term rates on US debt have started to creep up. They recently surpassed comparable rates in Canada, and even risk-taking investors are taking notice: “U.S. bond yields are attractive and interesting again,” indicated one analyst. Of course, when analyzing the recent increase in bond yields, it’s impossible to disentangle inflation expectations from concerns over default from optimism over economic. Nevertheless, the consensus is that rates/yields can only rise from here: “The CBO [Congressional Budget Office] estimates that interest rates on 3-month bills and 10-year notes will reach 5.0% and 5.9%, respectively, by 2020.”As if this wasn’t enough, the exodus out of the US Dollar over the last few decades has virtually ceased, with the US Dollar still accounting for a disproportionate 62.7% of global forex reserves. Furthermore, economists are now coming out of the woodwork to defend the Dollar and argue that its supposed demise is overblown. At last week’s annual meeting of the American Economic Association (and in a related research paper), Princeton University economist Peter B. Kenen “argued that neither Europe’s nor China’s currency presents a valid substitute–nor an International Monetary Fund alternative to the dollar that was created some 40 years ago.” Even if the RMB was a viable reserve currency – which it isn’t – Kenen points out that for all its bluster, China has shied away from taking a more active leadership role in solving global economic issues.

In short, as I’ve argued previously, the Dollar is safe, not just for the time being, but probably for a while.

The Dollar finished 2010 on a high note, both on a trade-weighted basis and against its arch-nemesis, the Euro. Speculators are now net long the Dollar, and according to one analyst, it is now fully “entrenched in rally mode.” Never mind that its performance against the Yen, Franc, and a handful of emerging market currencies was less than stellar; given all that happened over the last couple years, the fact that the Dollar Index is trading near its recent historical average means that the bears have some explaining to do.

To be sure, none of the long-term risks have been addressed. US public debt continues to surge, and will not likely abate in 2011 due to recent tax cuts. Short-term interest rates remain grounded at zero, and long-term yields have only just begun to inch up, which means that risk-taking investors still have cause to shun the Dollar. Ironically, signs of economic recovery in the US have reinforced this trend: “The [positive economic] data, which one would ultimately assume is positive for the U.S., looks better for risk, which in turn puts downward pressure on the dollar.” Finally, the the Financial Balance of Terror makes the US vulnerable to a sudden decision by Central Banks to dump the Dollar.

So what’s driving the Dollar in the short-term? The main factor is of course continued uncertainty in the Eurozone over still-unfolding fiscal crisis, which is directly driving a shift of capital from the EU to the US. Next, the budget-busting tax cuts that I mentioned above are predicted to both boost economic growth and make it less likely that the Federal Reserve Bank will have to deploy the entire $600 Billion that it initially set aside for QE2. (To date, it has spent “only” $175 Billion in this follow-up campaign, compared to the $1.75 Trillion that it deployed in QE1). According to The Economist, “JPMorgan raised its growth forecast for the fourth quarter of next year to 3.5% from 3% as a result [of the tax cuts]. Macroeconomic Advisers, a consultancy, says the new package could raise growth to 4.3% next year, up from its current forecast of 3.7%.”

In fact, long-term rates on US debt have started to creep up. They recently surpassed comparable rates in Canada, and even risk-taking investors are taking notice: “U.S. bond yields are attractive and interesting again,” indicated one analyst. Of course, when analyzing the recent increase in bond yields, it’s impossible to disentangle inflation expectations from concerns over default from optimism over economic. Nevertheless, the consensus is that rates/yields can only rise from here: “The CBO [Congressional Budget Office] estimates that interest rates on 3-month bills and 10-year notes will reach 5.0% and 5.9%, respectively, by 2020.”

In short, as I’ve argued previously, the Dollar is safe, not just for the time being, but probably for a while.

No comments:

Post a Comment