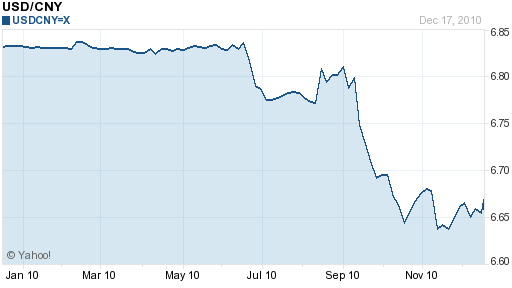

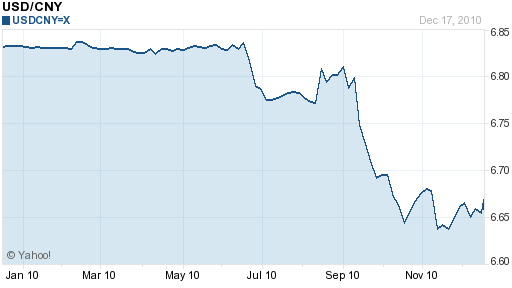

Based on nominal exchange rates, the Chinese Yuan has appreciated by a modest 2% against the US Dollar since the month of September (when the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) adjusted the currency peg for the first time in nearly two years). If you take inflation into account, however, the Chinese Yuan has risen by much more. In fact, if current trends persist, the Chinese Yuan exchange rate controversy might resolve itself.

Demands from the international community for China to appreciate its currency hinge on two related arguments. The first is that at its current level, the artificially low exchange has allowed China to build up a massive trade surplus. The second is that Chinese prices seem to be lower than they should be (when quoted in other currencies), and the economic principle of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) suggests that for this discrepancy to be eliminated, the Chinese Yuan must rise.

As it turns out, both of these claims are more problematic than they would appear. For example, China’s official trade surplus is already massive, and is steadily increasing. For 2010, it will probably near $200 Billion. However, it turns out that majority of that surplus is being captured by foreign-funded companies: “Their 112.5-billion U.S.-dollar surplus accounts for 66 percent of China’s total surplus over the past 11 months.”

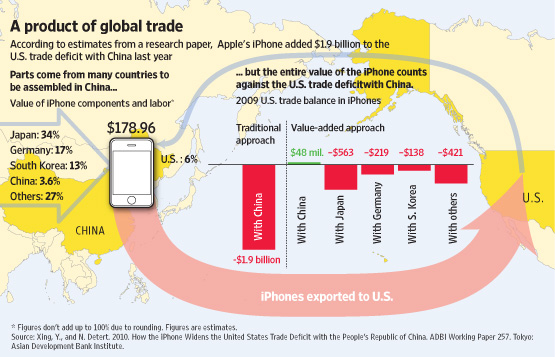

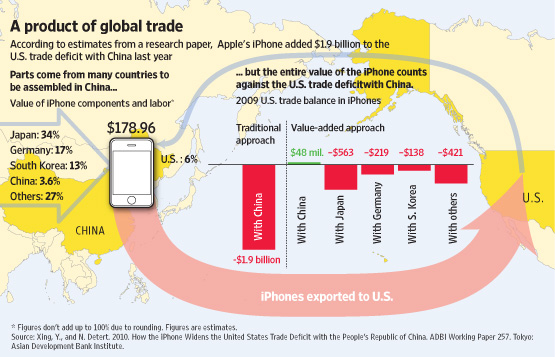

In addition, trade statistics are calculated in such a way that the country that assembles the finished product gets credit for the full export value of that product. By looking specifically at Apple’s popular iPhone, researchers calculated that the product officially contributed $2 Billion to the US trade deficit with China. When the nuances of the iPhone’s supply chain are taken into account, that figure swings to a surplus of $48 million. In both of these cases, the fact that these products are manufactured in China doesn’t detract from US GDP (though it probably does cost the US jobs). Hence, the US probably isn’t hurting as much from the weak RMB to the extent that some lobbyists insist.

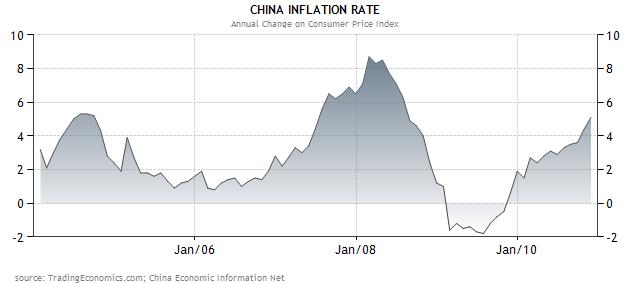

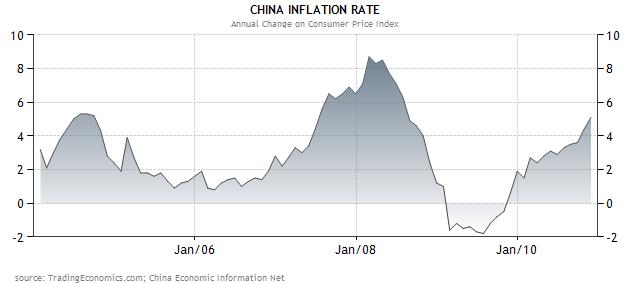

As for inflation, the official rate is now 5.1% on an annualized basis. Even if we accept this (and living in China, I can tell you that the actual rate is much, much higher), that means that the value of other currencies is eroding at a much faster rate than is implied by official exchange rates. That’s because a currency is only worth its purchasing power; as prices and wages in China rise, the purchasing power of the US Dollar (and other currencies) falls.

The Chinese government is trying to address the problem in the form of price controls and mandated increases in supply, but it is still reluctant to rein in inflation using conventional monetary policy measures. M2 money supply in China is increasing at a rate of 20% a year, the majority of which is being spent on another boom in fixed asset investment. While the PBOC has responded by increasing the required reserve ratio of Chinese banks, it remains reluctant to raise interest rates lest it contribute to further inflows of “hot money” on more upward pressure on the Yuan. As a result, the consensus among economists is that inflation will continue rising unabated: “We see a strong chance of underlying price pressures continuing to build over the medium-term.”

Unless circumstances change, then, the argument for further RMB appreciation is somewhat weak. Nonetheless, analysts remain optimistic: “A Bloomberg survey based on the median estimates of 20 analysts predicts the yuan to increase 6.1 percent to 6.28 percent by the end of 2011.” Given that Hu Jintao is schedule to visit the US in January – and China’s fondness for symbolic policy gestures – a token move of 1% or so before then wouldn’t be surprising. As for the predicted 6% rise next year, well, that depends on inflation.

Demands from the international community for China to appreciate its currency hinge on two related arguments. The first is that at its current level, the artificially low exchange has allowed China to build up a massive trade surplus. The second is that Chinese prices seem to be lower than they should be (when quoted in other currencies), and the economic principle of Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) suggests that for this discrepancy to be eliminated, the Chinese Yuan must rise.

As it turns out, both of these claims are more problematic than they would appear. For example, China’s official trade surplus is already massive, and is steadily increasing. For 2010, it will probably near $200 Billion. However, it turns out that majority of that surplus is being captured by foreign-funded companies: “Their 112.5-billion U.S.-dollar surplus accounts for 66 percent of China’s total surplus over the past 11 months.”

In addition, trade statistics are calculated in such a way that the country that assembles the finished product gets credit for the full export value of that product. By looking specifically at Apple’s popular iPhone, researchers calculated that the product officially contributed $2 Billion to the US trade deficit with China. When the nuances of the iPhone’s supply chain are taken into account, that figure swings to a surplus of $48 million. In both of these cases, the fact that these products are manufactured in China doesn’t detract from US GDP (though it probably does cost the US jobs). Hence, the US probably isn’t hurting as much from the weak RMB to the extent that some lobbyists insist.

As for inflation, the official rate is now 5.1% on an annualized basis. Even if we accept this (and living in China, I can tell you that the actual rate is much, much higher), that means that the value of other currencies is eroding at a much faster rate than is implied by official exchange rates. That’s because a currency is only worth its purchasing power; as prices and wages in China rise, the purchasing power of the US Dollar (and other currencies) falls.

The Chinese government is trying to address the problem in the form of price controls and mandated increases in supply, but it is still reluctant to rein in inflation using conventional monetary policy measures. M2 money supply in China is increasing at a rate of 20% a year, the majority of which is being spent on another boom in fixed asset investment. While the PBOC has responded by increasing the required reserve ratio of Chinese banks, it remains reluctant to raise interest rates lest it contribute to further inflows of “hot money” on more upward pressure on the Yuan. As a result, the consensus among economists is that inflation will continue rising unabated: “We see a strong chance of underlying price pressures continuing to build over the medium-term.”

Unless circumstances change, then, the argument for further RMB appreciation is somewhat weak. Nonetheless, analysts remain optimistic: “A Bloomberg survey based on the median estimates of 20 analysts predicts the yuan to increase 6.1 percent to 6.28 percent by the end of 2011.” Given that Hu Jintao is schedule to visit the US in January – and China’s fondness for symbolic policy gestures – a token move of 1% or so before then wouldn’t be surprising. As for the predicted 6% rise next year, well, that depends on inflation.

No comments:

Post a Comment