Last week, S&P fulfilled rumors by lowering the Sovereign credit rating of Japan. The move immediately sparked headlines filled with words like “roil” and “turmoil,” and analysts predicted the beginning of a massive correction, like the kind that I forecast in January. I decided to wait a few days before posting on this story, in order to wait for the dust to settle. I’m glad I did, since the Yen’s stubborn refusal to slide further beggars some kind of explanation!

In hindsight, the Yen’s 1% fall during that day’s trading session was modest by any standards, despite the financial media’s attempt to characterize it as extraordinary. Even those analysts which conceded that the decline in the Yen was pretty mundane argued that depreciation would begin in earnest after the forex markets had a chance to digest the full impact of the downgrade. Simon Derrick, senior currency strategist at Bank of New York Mellon told the Wall Street Journal, “I would not be surprised if there is a second wave of yen weakness associated with the New York open.”

As much as one would have expected the downgrade to make a bigger splash, there are a couple of explanations for why it didn’t. First of all, the move was relatively modest – from AA to AA- – and S&P indicated that there wasn’t any risk of further downgrades in the immediate future. Second, as I reported in mid-January, rumors of a rating cut have been circulating for quite some time. When you look at the abysmal state of Japanese government finances, it was really only a matter of time before the rating agencies woke up to reality. Japanese public debt is projected to reach a whopping 204% of GDP this year, and according to S&P, it has no “coherent strategy” to address the problem.Most important, the majority of Japan’s sovereign debt (~95%) is held by domestic investors, which means that the impact of any foreign capital flight would have been extremely limited. Due to perennially low interest rates, Japanese savers have few options but to stash their cash in Japanese government bonds, the yields on which hardly budged as a result of the downgrade and are still extraordinarily low.

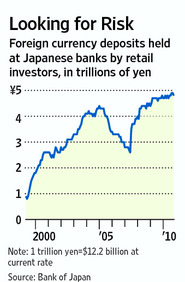

It’s hard to say whether this situation will change. On the one hand, a substantial portion of Japanese investors seem to recognize that keeping money at home is a losing proposition. “According to the Bank of Japan, individuals held about 4.83 trillion yen ($58.87 billion) in foreign-currency deposits at Japanese banks as of the end of November last year, up 2.8%from a year ago and the highest since the central bank started providing the data in April 1999.” Due to an aging population, increased appetite for risk, and widening yield differentials, this trend is projected to continue for the immediate future.

On the other hand, all of this capital outflow is necessarily already reflected in the Yen, which has remained strong in spite of the carry trade. Perhaps the Japanese economy has been underestimated. While the current account surplus has showed signs of narrowing, it nonetheless remains a surplus. Perhaps that’s because Japanese companies are have proven that they are capable of adapting to the rising Yen, by either lowering costs or shifting production abroad. While Japanese retail investors move money abroad, Japanese companies are repatriating a steady stream of profits back home.

No comments:

Post a Comment